Guest post by:

Sofia Bartlett PhD

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Clinical Prevention Services at the BC Centre for Disease Control & Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, UBC

Since COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020, there has been an intense focus on locations where the SARS-CoV-2 virus seems to transmit more frequently or cause more deaths, such as long-term care homes and cruise ships.

These are congregate settings, where many people are brought together in close quarters, with typically a high proportion of older people who are more likely to have chronic health conditions making them more susceptible to severe COVID-19 disease.

Another congregate setting which has also been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, but has not received as much attention, is prisons. Prisons also tend to bring together people with poor health, and environmental factors specific to correctional settings, such as crowding, aging infrastructure, and lack of sanitation, increasing the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission.

These factors mean that prisons could be a ‘petri dish’ for COVID-19 if they do not receive adequate attention and support to deal with the pandemic.

Early identification and containment of SARS-CoV-2 spread in federal correctional facilities during the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020 was effective in restricting outbreaks to 5 of 43 correctional facilities. In provincial correctional centres, where people who are unsentenced (on remand), or have a sentence of less than two years, are incarcerated, in Quebec, 105 people who were incarcerated and 51 correctional employees in 9 provincial prisons tested positive, and ten people in Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta testing positive, in provincial correctional centres.

This means that in the first COVID-19 wave in Canada, the rate of infections detected behind bars was up to nine times higher than that in the general population.

Infections detected in the first COVID-19 wave in the general population were just the tip of the ice berg though, with the extent of undetected infections being as high as 8 times greater than the number reported by health authorities. The extent of undetected previous SARS-CoV-2 infections in correctional centres across Canada in both federal and provincial institutions remains unknown though, and cases in prisons during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada are surging.

So that’s why investigators at the BC Centre for Disease Control, University of British Columbia and BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services launched a BC Provincial Corrections COVID-19 antibody prevalence study.

The study aims to determine if people who are provincially incarcerated or work in provincial corrections in BC have the same or higher prevalence of antibodies against COVID-19 as the general population, and what the predictors of having COVID-19 antibodies are in these groups. We are also asking people about their experience of being incarcerated during this global pandemic, how the different measures put in place in correctional centres to COVID-19 may have impacted them, and if they plan to accept an approved COVID-19 vaccine if or when it’s offered to them.

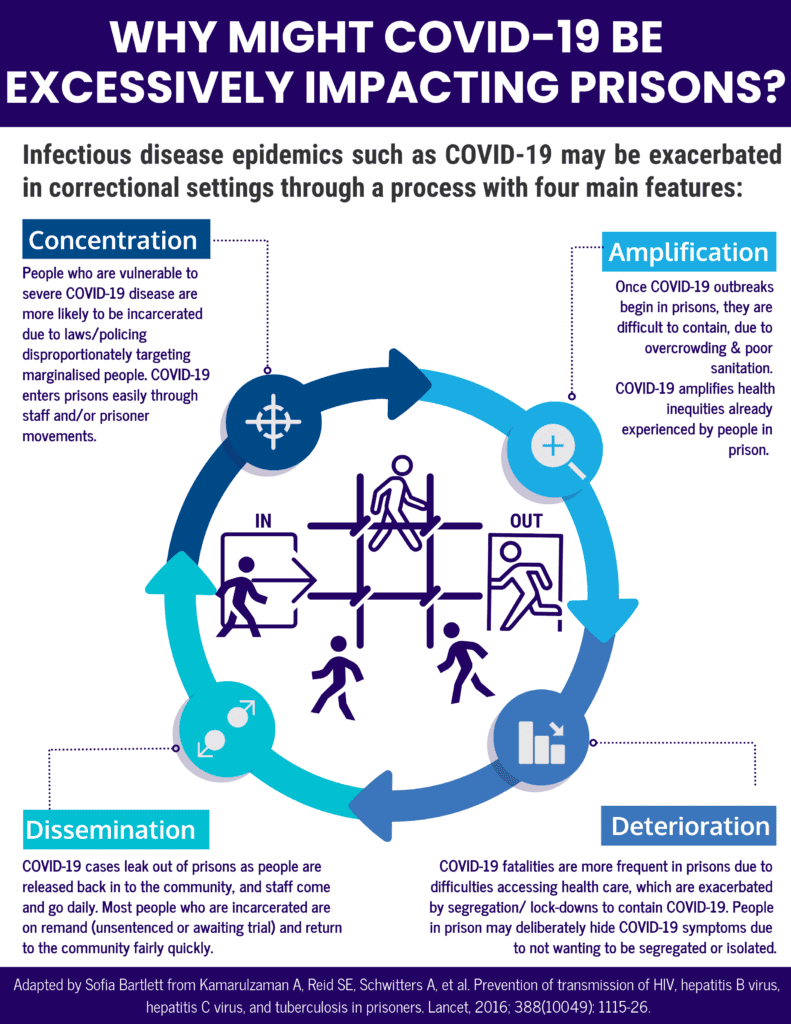

It’s important to do studies such as this, so we can uncover the extent to which COVID-19 has excessively impacted prisons in Canada, and determine what the drivers of these impacts are. We already have a hypothesis to explain the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on people in prison, which is based on previous epidemics that have disproportionately impacted people in prison, such as HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis.

By determining if this hypothesis is correct, it will allow interventions to address or prevent these impacts to be designed and implemented. The current hypothesis is that a process of disease Concentration, Amplification, Deterioration, then Dissemination has been occurring in the correctional system during the COVID-19 pandemic.

People in prisons across Canada have disclosed that the health care system behind bars is failing, and they fear they will not leave prison alive. Segregation is being used for medical isolation or quarantine during COVID-19 as prisons have few other options available to them, and Canadian prison advocates and watchdogs have called the overuse of segregation during the COVID-19 pandemic ‘atrocious’ and potentially a Charter rights violation.

In person educational and rehabilitative programs, as well as family visits, have been suspended in most prisons in Canada for 12 months now, casting doubts on the correctional system’s ability to function as a place of rehabilitation during pandemics. While efforts to de-carcerate were made early in the first COVID-19 wave, daily prison counts began to creep up across Canada in the second half of 2020 and researchers and advocates are calling on governments to focus on this action again.

The spread of COVID-19 behind bars is not inevitable—with appropriate actions, the cycle of Concentration, Amplification, Deterioration, then Dissemination can be broken. Prison health is an essential component of public health, and responses to COVID-19 in prisons are a vital component of effectively controlling the virus to protect all of us.

Interesting in reading Dr Bartlett’s guest post “Addressing Barriers to Sexually Transmitted and Blood Borne Infection (STTBI) Screening and Care in Prisons”? Go here to read her article.